Bima Satria Putra

Bakunins Ghost and the 1926 Indonesia Communist Uprising

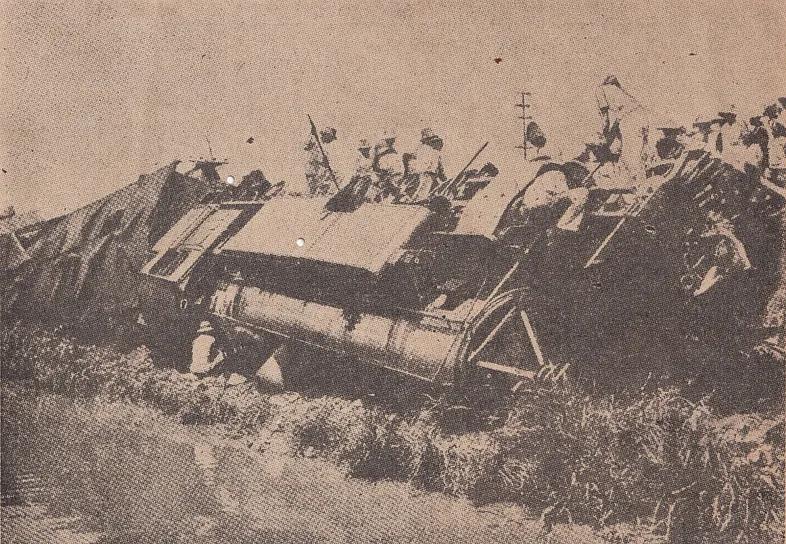

On November 12, 1926, the Dutch East Indies colonial government was hit by a nationwide rebellion by the communist party. The rebellion did not occur all at once and lasted until 1927 in Sumatra. At that time, the communist parties in the Dutch East Indies were heavily influenced by the idea of anarchism.

Arif Dirlik stated that, “anarchism was the dominant ideology during the first phase of socialism in East Asia.”[1] Studies of anarchism in India, the Philippines, Malaysia, Korea, Japan, China, Vietnam and even Timor Leste, have been well described. However, Indonesia is a different story. According to Klaas Stutje, no self-conscious anarchists, in an ideological sense, in the first decades of the 20th century, were known in the Dutch East Indies.[2] Despite efforts to organize branches of Dutch Christian anarchist as well as Chinese immigrant anarchists, anarchism was never promoted openly within indigenous political organizations. Why is that? What can explain this emptiness?

In 2018, I explained the best possibility of this in the book The War We Won't Win: Anarchism and Syndicalism in the Anti-Colonialism Movement in Indonesia (1906-1946). Even though there is a lot of raw data, I will try to explain that “there is no anarchist movement in Indonesia.” More precisely, the idea of anarchism was integrated into the widespread socialist political movement, and later, became only an element within the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI).[3] All ideas of socialism, whether those of Bakunin, Proudhon or Marx, as long as they fight against anti-colonialism and serve as a means of struggle, will be presented on one plate under the name “socialism/communism.”

The conclusion is that the socialist movement in Indonesia is actually eclectic. It is quite possible that, as in many world cases, a movement figure who is spontaneously anarchistic, or consciously sympathetic to anarchists, calls himself simply a socialist, communist or nationalist. In fact, the socialist movement before 1918 did not distinguish between "social democrats" and "communists" as it does today. Bakunin's internal faction in the First International bore the name Social-Democrat. It was only after the militant current of the Russian Social Democrats changed its name to the Communist Party in 1918, and militants in other countries followed suit, that a distinct communist identity emerged.

Socialism had been introduced since the turn of the 20th century, then organized after Dutch socialist Henk Sneevliet initiated the Indische Sociaal Democratische Vereeniging (ISDV) in 1912 which six years later became the PKI, the first communist party in Asia. Although ISDV leaders directed the organization to stick to Marx-style Communism, historian Saul Rose explains that in Indonesia, “Bakunin's ideas were also popular.”[4]

Jeanne S. Mintz in her study of the emergence of the socialist movement in the Dutch East Indies stated that many Indonesian socialists seemed to be more familiar with the works of Utopians and pre-Marxist collectivists: constitutes a mixture of the most heterogeneous, such as the works of Domela Niuwenhuis, Henriette Roland Horst, the writings of Bakunin and many others written about him.”[5]

The existence of anarchist books in the Dutch East Indies as reported by Mintz above has been confirmed. For example, if you go to the National Library of Indonesia in Jakarta, you will find a biography by Max Netlau entitled Michael Bakunin: Eine Biographische Skezze, published in 1901. The memoir of the Dutch anarchist Ferdinand Domela Niuwenhuis entitled Van Christen tot Anarchist was once reviewed on the front page of local newspapers in 1911, just months after the book was first published.[6] According to de Tollenaere, two of the earliest figures of the Dutch anti-colonial movement Ernest Douwes Dekker and Mas Marco Kartodikromo were influenced by Domela.[7] Marco cites that book in writing at Sinar India [The Light of the Indies][8] and quoted Domela in her defense when her writing was questioned by the government.[9] Marco repeatedly quotes Domela on many occasions and Marco is politically aware of this: “He is a Domine [priest] who eventually becomes an anarchist, and goes to prison several times, because he will help people who are in trouble, aka those preyed upon by other fellow humans.”[10]

Along with the growth of indigenous movements, the notion of anarchism is one that is discussed and discussed by movement activists. Oemar Said Tjokroaminoto, who is known today as the Indonesia “Founding Father of the Nation”, was one of the figures involved in this process. He played a role in the reorganization of the Sarekat Dagang Islam into the Sarekat Islam/Islamic Society (SI) in 1912. SI was a politically plural organization. Colonial official and journalist Kiewiet de Jonge in his writing in Indische Stemme [Voice of the Indies] stated that SI consisted of “anarchists, socialists, nationalists (bourgeois), religious people, etc.”[11] Tjokroaminoto himself in his view of the ideal form of government called the Islamic State should refer to the “independent ummah” in the city of Medina during the leadership of the Prophet Muhammad, which is described as:

“...a Kingdom (staat)... who do not need to use power and police force to keep them in order, are people who do not harbor feelings of hatred among one another because of differences in national class or skin color, are the people among whom there is no difference between those who rule and those who are ruled.”[12]

It is clear that to some extent Tjokroaminoto was influenced by anarchist conceptions of freedom and equal rights, so that the SI statute emphasized the aim of “liberate all people from any form of bondage.”[13] In fact, SI does study anarchism in its education program. This was recorded from the experience of the Indonesian cleric Buya Hamka in the introduction to Tjokroaminoto's biography. When he migrated to Java, Buya Hamka took part in various SI courses in Yogyakarta in 1924. One of his teachers was Tjipto Mangunkusumo, who provided material on Islam and socialism. “At that time I began to know communism, socialism, nihilism. It was then that he began to hear the names of Karl Marx, Engels, Proudhon, Bakunin, and others,” wrote Hamka.[14]

As a result of the ISDV's influence, SI, under Tjokroaminoto's leadership, began to show his socialist character. Unbridgeable divisions have divided this organization into two camps: White SI and Red SI. In 1924, Red SI became the Sarekat Ra’jat or Peoples Union (SR) and continued to maintain official relations with the PKI. In essence, the PKI-SR was seen as a patronage relationship between political parties and a mass base. Wherever SR was established, branches of the PKI had to be established and through SR, finally, the PKI began to have a peasant base. This revolutionary character of SI will be maintained in SR. Iwa Kusumasumantri, a law student in Leiden and then in Moscow in 1927 in a study of the peasant movement in Indonesia, stated that “both in the Communist Party and in the People's Sarekat, a very strong anarchist deviation was observed.”[15]

While Tjokroaminoto decided to enter parliament, the students who had lived with him then crossed the all political spectrum and did not always align with him. Kartosuwirjo represented the Islamic group, Alimin and Musso the communists, and a future first president of newly independent Indonesia Soekarno himself was a nationalist. During his high school education in Surabaya, Soekarno stayed at Tjokroaminoto's house where he met several left-leaning Indonesians and Dutch. In Bandung, he met librarian Daniel Marcel Koch. Koch is known to have introduced the works of Kautsky and Bakunin to Soekarno.[16] Sukarno himself eloquently published two articles on anarchism in 1932.[17]

Other Tjokroaminoto students who deserve attention are Alimin and Musso. Both were young militants who joined SI, ISDV and nationalist organization Insulinde at once, which brought their loyalties into question. When the ISDV turned into the PKI, Alimin left the trial which was heated. It seems that Alimin decided to leave ISDV, because other sources state that he joined the PKI (again) in December 1923. Alimin remained steady there, leaving SI and Insulinde. Even so, “the PKI leaders suspected... they were known as anarchists and especially Alimin was personally very attached to Tjokroaminoto and Salim,” wrote Harry A. Poeze.[18]

There is widespread agreement among historians regarding the “deviations” within the first generation of the PKI. Although the PKI declared official affiliation with the Comintern in Moscow, the domination of the spread of anarchist ideas was almost unstoppable. After Soe Hok Gie examined various newspaper clippings from 1917-1920's for his baccalaureate thesis, he observed that within the PKI, “what they understood to be Marxism, was difficult to account for as Marxism.”[19]

In his autobiography, Alimin also acknowledged the existence of political diversity within the PKI. “At that time, the party still had various currents: anarchist, socialist, nationalist, and communist. In short, at that time the PKI was not yet a real communist party on international standards.”[20] The PKI Historical Institute in the Pemberontakan Nasional 1926 [1926 National Uprising] confirmed that there was a "weakness in the field of mastery of Marxist-Leninist theory as a form of ideology and a weapon of working class theory," and that “the books of Marx, Engels and Lenin could not yet be spread as reading material for PKI leaders and cadres.”[21] At that time, the Karl Marx's Communist Manifesto were only translated in 1924. Other writings by Marx were still in English and Dutch, poorly understood and unreachable.

Alimin never claimed to be an anarchist. But he did admit that when he was young: “we wanted to 'become communist'. We read a book or two,” and “in the Far Lands [of the Soviet Union] we could understand what rank and power meant.”[22] The newspaper that Alimin managed, Sora Merdika [Voice of Independence] once discussed Bolshevism in 1920. Its author, the editor-in-chief of the newspaper, wrote: “I have not been able to determine whether this movement is good or bad, because until now I have not been able to evaluate or prove bad and his evil, or his good and glory.”[23] Thus, although Lenin and the Bolshevik Party had inspired as examples of the success of the revolution, the basic principles of Marxist-Leninism were understood only quite late. The Russian Revolution of 1917 did not spontaneously lead to the process of Leninization of the early left movement in the Dutch East Indies for granted. Soe Hok Gie himself was of the opinion that, “the issue of foreign influence is still being greatly exaggerated.”

If not Marx, then what kind of socialism studied by party leaders and cadres? The only way to answer this is to look at published writings. The problem becomes rather complex, because according to McVey, the decentralized character of the communist press in the Indies makes each local media reflect the popular thoughts and approaches of the local party leaders who run it. In 1926 there were an estimated 20 party media by the central office and branches which were banned after the rebellion.[24] This does not include media that were banned or previously bankrupt, as well as the media of trade unions and other communist-sympathizing organizations. Each media conveys various aspirations, and even in one medium it is sometimes contradictory depending on the author.

Even so, this does not mean that a cursory review of the dominant non-Marxist ideas within the PKI is impossible. What has been identified so far is at least divided into three main categories, namely Bakunin's anarcho-communism, nihilism, and anarcho-syndicalism.

Until now, no writings on syndicalism have been found, let alone in Indonesian, except for writings in Dutch by Ernest Douwes Dekker. But in local writings, socialism is understood in a very libertarian vein. For example, Tjokroaminoto in his book Islam dan Sosialisme (1924) describes anarchism as a type of socialism, which “demands that...all means of making goods (production) should belong to the vakvereeninging (workers) associations.”[25] This syndicalist definition of socialism will often be found in other writings, even up to the beginning of independence.

This legacy is still strongly felt in Musso's writings. Not much of Musso's writing remains from his youth. He then studied Marxism in Moscow and was only able to fully return to Indonesia in 1946. Seeing the chaos of the communist movement in newly independent Indonesia, prompted Musso to call for the unification of various communist factions in a single PKI party. This proposal was published in the pamphlet Jalan Baru [New Road] in 1948. In that article Musso emphasized workers' control, repeating the anarchist definition of Tjokroaminoto written decades earlier: “that production must be increased as much as possible on condition that the production and distribution and trade of goods belonging to the state must be supervised by the trade unions.”[26] It is therefore natural that Mohammad Hatta once judged that Musso “was more like an anarchist than a communist.”[27] As Vice President, Hatta later rejected workers' control in Indonesia's post-independence economic planning, repeatedly emphasized that means of production and transportation such as railroads must be under state control by warning workers “not to mistake syndicalism for economic democracy and arbitrarily replace officials without the knowledge or approval of the government.”[28]

Syndicalism in the Netherlands is quite strong among railroad workers. It is clear, that they are worth tracing as carriers of this idea while working in Indonesia. “In the history of syndicalism in Indonesia,” wrote Leclerc, “revolutionary syndicalism that is anti-colonial and anti-capitalist, as well as the history of communism in Indonesia, has always had formatters originating from the railroad workers.”[29] Iwa Kusumasumantri also stated that, “there is no doubt that there are very serious syndicalist tendencies among some of the leading comrades.” Syndicalist tendencies were warned by the newspaper Njala [Ignite], which was published by the Batavia branch of the PKI.[30]

Railway workers were the pioneers of the labor movement in the Dutch East Indies at that time. Spoorbond was the first labor union in the Dutch East Indies, formed in 1905. Due to its reformist orientation, four years later Vereniging van Spoor en Tramwegpersoneel (VSTP) was founded by the 1960s by railroad and tram workers from three companies. When the union was founded, Dutch syndicalism was at its peak within the NAS federation.

Almost as much as Marx, writings about anarchism and nihilism are also often found. After Soe Hok Gie examined various newspaper clippings from 1917-1920's for his baccalaureate thesis, he observed that within the PKI:

“These 'Marxist' concessions are a clear reflection of nihilist tendencies. They are aware that in order to fight against oppression, if necessary they will carry out underground movements and covertly promote terror.”[31]

Soe Hok Gie refers to the commentary on acts of political violence written by Darsono when he joined the Sinar Djawa [Light of the Java] editorial team. Using the pseudonym Onosrad he wrote a series of articles about the Russian nihilist movement which appeared irregularly from 21 March 1918. He recounted with impassioned writing the heroism of the nihilist Vera Zasulich, Arkhip Bogolyubov, and Sergey Nechayev in the struggle against the Tsarist dictatorship.[32] Darsono also treats the same thing to Mikhail Bakunin in another article entitled “Laying down the Government.”[33]

An article published in Sora Merdika [Voice of Indepence], entitled “Dunia jeung Jaman Anyar” [New World and Age], has treated anarchism and nihilism as synonyms delimited by italics (/). Described as “two schools of thought that cannot be separated,” with the intention of “killing kings... replacing the government and the lives of its people, with rules and traits that are based on humanity.”[34]

All socialist traditions are mixed up in the horizon of the first left movement and the references are not limited to Karl Marx alone. One editorial in Sinar India [Light of the Indies] in 1924, for example, which was the official organ of the SR, expressed admiration for the French non-Marxist socialist Auguste Blanqui, who campaigned for direct action and armed rebellion. The editorial urged the program of “revolutionary political violence”, which was likened to when the proletariat came to its enemies “like a whirlwind” that would destroy them and reach communism. [35]

Figures of anarchism are sometimes framed with positive connotations. Soeara Ra’jat [Voice of the People] openly explained that Marx and Engels were PKI teachers, not Bakunin, who was once one of Marx's greatest enemies. Even so, the writer flattered: “We will also honor his name, because of his services, which are enormous. Bakunin, a nobleman.. he moved and fought for the rights of the oppressed, so that he was jailed more than once.” The author explains that Bakunin was not a communist, but an anarchist.[36]

Of course, it seems that the article received such a response that an article on anarcho-communism appeared in Soeara Ra’jat a month later to set the record straight. The writer under the pseudonym Mahatma Moerti, staunchly defends that anarchism is part of the socialism. He mentions the names of world anarchist figures who make us wonder what his reading sources are: Errico Malatesta and Carlo Cafiero (Italy), Élisée Reclus (France) and Peter Kropotkin (Russia).[37] In addition to the names above, many years earlier, a writer with the pseudonym Karjadipa also discussed socialism, citing the French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in Sinar Djawa without criticism.[38]

From the published writings it can be seen that anarchism is interpreted on two levels. The first, as part of the socialist ideology which proposes joint ownership of the means of production, through workers' control and the results can be used by many people. This was popularized in the motto: sama rata, sama rasa (“Equal, Same Taste).” McVey himself, concluded that the PKI's popular image of communism and revolution, was far from being Marxist:

“This revolution does not need the dictatorship of the proletariat or any other intermediate stage; headed straight for a classless society in which the state was replaced by voluntary mutual assistance. The PKI leaders did not think to talk about governing a state after liberation from the Dutch; they discovered a utopia, the nuances of which their followers could interpret as they liked.”

“...under Communism, there will be no more economic or political competition: everything will be based on cooperation. There will be no poverty. People will work because they want to and at tasks they enjoy; there would be no masters, no servants, and no seeking of profit. Government problems would be easily solved, for there is no need for an army or navy, no legal property rights, no laws other than customary law, no prisons, orphanages or other apparatus of an exploiting state.”[39]

All the ideals of the post-revolutionary society that the CPI widely promoted to the Dutch East Indies audience had anarchist ideals. Of course, the name of Marx is mentioned, but not the theory of Marxism. Communism understood in the Dutch East Indies was not the Marxist-Leninist type of communism which officially became the axis of the PKI in the 1940-1960's decade, but anarcho-communism. The Marxist conception of usurpation and workers' government only appeared since 1924, particularly through the wire news about Russia. The effect is too late.

Second, anarchism is understood as an anti-government and anti-feudalist ideology, and wants to eliminate it through acts of violence, murder, and armed rebellion. Anarchism then became synonymous with chaos and violence, acts of terror on personal initiative, disorganization or lack of party discipline, and it just stopped there. Apart from the mainstream media, the term with this meaning is used by communists with a more mature Marxist theory, including party members and movement activists from other organizations.

In these two levels anarchism colors the discourse of the communist movement in Indonesia. The first is the goal to aim for, and the second is the way to achieve that goal. Anarchism, which is understood as a method, is well established in Surakarta. According to Soe Hok Gie, Sophia Perovskaya's nihilist bombings inspired a series of sabotage, arson, property destruction and bombings between 1923-1926, which led to the exile of Haji Misbach, a leader of the communist movement in Surakarta to Digoel.[40] Larson also stated that the terrorist activities of the communists in Surakarta marked the influence of anarchism.[41]

The efforts of PKI leaders to dampen the influence of anarchism have been well documented. Even though they do not agree with acts of terrorism, on many occasions many of them accept it as an inevitable result of repression.

However, some central PKI leaders viewed the bombing with dismay. For example, Seemaun. As a result of the failed VSTP strike, he had to leave for exile to the Netherlands in August 1923. But before that he had attended the PKI and SI-Merah congresses in March 1923 in Bandung. At the congress, Semaun made a speech: “The spirit of communism has been instilled in the hearts of the people. Our goal is not to follow in the footsteps of anarchism, but the path to real communism.”[42] The PKI executive leadership felt that the party needed to be disciplined, strengthen the party's control over the masses, and become involved in parliament. After years of existence, the PKI only adopted Marxism in the party statutes officially through this congress. Its implementation did not go smoothly. The Marxist course was not effective and this also did not stop acts of terrorism and anarchist agitation in the party press.

In a general meeting on 28 October 1923 in Semarang, Darsono repeated Semaun’s call that the party under no circumstances should fall under the temptation of terrorism. Darsono said the PKI had to follow Marx’s communism, not Bakunin’s anarchism. Darsono said that anarchism is an ideology that teaches that a group of 100 to 200 people can take power if they dare to kill the king and ministers with a bomb. “The person who threw the bomb is a person who can be said to be very brave, who does not back down in the face of arbitrary actions. I give my respect to the person who has shown his courage in expressing his humanity in this way,” he said. However, in his opinion bombings were “unacceptable to the communists and inconsistent with communist political lines.” According to Shiraishi, Darsono was well aware that the PKI/SI Merah propagandists were the ones who carried out the bombing and that was the reason Darsono was careful not to denounce “anarchists” directly.[43]

Until now, there has not been found any written evidence of PKI members declaring themselves to be anarchists. All these claims come from members of other parties, labels by the mass media, suspicions of government reports, and conclusions from historians. For example, McVey said that Pieter Bergsma, a member of the VSTP and secretary of the PKI, had syndicalist tendencies.[44] For native workers, Leclerc mentions several names of syndicalists: Winanta, Hindromartono, Djokosudjono, and Semaun.[45] All were railroad trade union militants, refused participation in parliament, advocated direct action, and all were PKI leaders at different times. This requires further investigation, especially when Semaun was young, before becoming a genuine Marxist under Sneevliet's upbringing.

One of the most prominent PKI leaders at this time was Herujuwono from the Batavia branch, who, according to McVey, was most eager to encourage armed rebellion.[46] Later, he led the command of the rebellion in West Java, the decision of which was taken at the Prambanan conference in December 1925. At the conference, Sardjono as the central administrator of the PKI and other speakers explained that matters had reached the point where it was necessary to make a real plan for the rebellion. Sardjono suggested that this action should start with a strike and culminate in protracted violence, with attempts being made to draw peasants and soldiers into rebellion on the Communist side.

On the same date, the VSTP congress took place at the Pasar-Pon Hotel, Surakarta. The leaders discussed plans for a strike that would end in an uprising. The minutes of the congress listed the names of thirty-two VSTP/PKI leaders who were deemed to show dangerous anarchist tendencies.[47] McVey saw this as a manifestation of the note's concern for irresponsible radicalism within the organization.

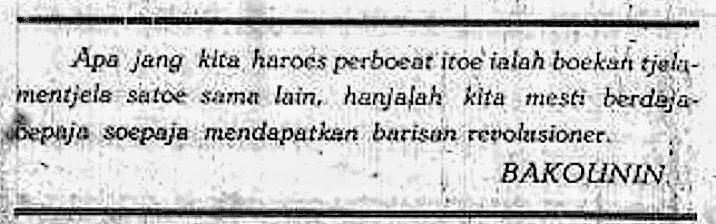

By the end of 1925, the PKI had lost many leaders who had good Marxist understanding, such as Sneevliet, Darsono, Semaun and Tan Malaka. All of these leaders have been exiled, not including the PKI leaders who were imprisoned and exiled to Digoel. Sinar Hindia which later turned into Api [Fire], namely the official organ of the PKI published in Batavia, then under the control of Herujuwono. Beginning with the issue of January 2, 1926, Api published a quote from Bakunin on the character of the revolutionary action, italicized and capitalized on the first page; “Nothing like that had happened then for any other political thinker,” McVey commented.[48] This guide clearly violated Semaun's and Darsono's warnings two years earlier that the PKI had to follow the political line of Marx, not Bakunin.

The rebellion plan was opposed by Tan Malaka. He wrote several pamphlets harshly criticizing how “members of anarchist blood go their own way and persuade their comrades.” He also asserted: “Mass-action knows no idle fantasy of a putch or an anarchist or the courageous act of a hero.”[49] The PKI rebellion was brief and messy, resulting in 20 thausand people were detained and of that number 1308 people were exiled to the Boven Digoel camp, Papua. While 20 people were executed throughout the Dutch East Indies. The PKI had to go underground and only emerged in 1946, less than a year after Indonesia declared its independence.

After the PKI rebellion in 1926, agitation and anarchist coverage in the movement's media almost completely disappeared as the rebels were exiled to Digoel. “The anarchists who were anti-parliamentary had less and less influence and are now almost meaningless,” wrote Mohammad Hatta in 1931, “while the social-democrats who are parliamentary leaning are getting stronger and stronger.”[50] In 1951, PKI general secretary DN Aidit confidently declared the PKI bolshevik leanings:

“Apart from that, these are also the remnants of our own Party's past, the era when anarchist elements more or less still reigned in our party... But now our Party is different... Gradually our Party already bolshevied themselves, not only in the political, ideological and organizational fields, but also in the moral field.”[51]

While the first generation of the PKI openly condemned PKI members with anarchist tendencies as the cause of the movement's downfall, the second generation in the 50-60's did the exact opposite. Under the leadership of DN Aidit, the party's historical institute published an official book on the uprising, lauding it as “the uprising that shook the foundations of Dutch imperialism.”[52] It does not mention anything about the influence of anarchism, nihilism, and syndicalism. They disguise him as a “leftist” “petty bourgeois intellectual”. What led to such a serious simplification?

The PKI, which existed in the decade of the 60's, was in In the midst of the struggle for national political influence and the tension of the cold war situation. They did not miss this historical material. The PKI packaged it as a form of the real contribution of the communists in the struggle for independence. The party's official book on the topic emphasizes the rebelion as the first national-scale uprising, and is proud of it. Pushing anarchism into a corner is tantamount to giving the stage for the influence of anarchism and belittling the early Marxist figures (Sneevliet, Darsono, Semaun, Tan Malaka) who were actually the most persistent in resisting and instead tried to thwart plans for rebellion.

After all, the objective judgment of historians knows who should be held responsible. McVey wrote:

“...the party sowed the seeds of its own demise, showing the danger of relying too heavily on the anarchist elements that were part of the appeal of communism: the price for the PKI's popularity was the promise of revolution, and eventually found itself leading an uprising whose leaders knew would not succeed.”[53]

Many historians agree that anarchism existed in the popular movements of the time. But it is simply framed as a “tendency”, or “deviation”, or “element”, or Klaas Stutje calls it: “ghost.”[54] In his review of McVey’s book, Harry J. Benda reiterates: “It was the ghost of Bakunin, not Lenin, who haunted behind Prambanan’s fateful decision to launch an armed uprising.”[55]

In this case, Indonesia is not a unique. During the first two decades of the 20th century, the spread of anarchism allowed us to glimpse what Arif Dirlik called “the regional dynamics of radicalism”[56] in East Asia that prevailed in Japan, China, Korea to Vietnam. In Saul Rose's terms, the dominant thought in the Dutch East Indies at the beginning of the 20th century he called “radical extremism.”[57] Takashi Shiraishi called it “popular radicalism.”[58] Whatever the term historians use, the meaning is more or less the same. Anarchism plays its role in critique of domination, alternatives to coercive and exploitative institutions, and confrontation with colonial powers.

The theoretical exploration of early communist activists resulted in a political anomaly phenomenon that was influenced by anarchism, but at the same time was not an anarchist movement. Anarchism has left a deep impression (deeper than I have ever thought) in the early third decade of the 20th century. Its can be traced in all expressions of existing political blocs, starting from Islam (SI), nationalists (Indische Partij) and communism (PKI). With this understanding, it is appropriate to call anarchism a ghost, the driving force for Indonesia's first national-scale premature rebellion.

Notabene

The minutes of the VSTP congress which took place at the Pasar-Pon Hotel, Surakarta on 25-26 December 1925 included a list of 32 high-ranking PKI/VSTP people with anarchist tendencies. I'm looking for access to the archive and will update this post if I get one. Meanwhile, on August 9, 1927, the De Locomotief newspaper in Semarang published a list of exiles to Boven Digoel. Some of them from Surakarta, identified as anarchists, namely:

-

Kartowihardjo, alias Soewandi (30 years), cloth trader, Sarekat Ra'jat administrator, anarchist.

-

Alisoewarno alias Salim (24 years), cloth printer, member of the Solo Batik Workers Union, one of the heads of the anarchist section of the PKI.

-

Sahirman (20 years), former employee of the State Railway Company, propagandist of Sarekat Ra'jat, secretary of Sarekat Tani, anarchist.

-

Djojosoekarto alias Ismangoen (30 years), shoemaker, Sarekat Ra'jat administrator, anarchist.

-

Darmosoetjitro alias Darmodjo (40 years), stamp maker, Sarekat Ra'jat administrator, anarchist.

This article is dedicated to the names above, the ghosts that history has missed.

[1] Arif Dirlik. “Anarchism and The Question of Place: Thoughts From The Chinese Experience”, in Anarchism and Syndicalism in the Colonial and Postcolonial World, 1870–1940 (2010), pg 134.

[2] Klaas Stutje. “‘Volk van Java, de Russische Revolutie houdt ook lessen in voor U’: Indonesisch socialisme, bolsjewisme, en het spook van het anarchisme” in Tijdschrift Voor Geschiedenis (2017), pg 440.

[3] Bima Satria Putra. Perang yang Tidak Akan Kita Menangkan: Anarkisme dan Sindikalisme dalam Pergerakan Antikolonial hingga Revolusi Indonesia (1908-1948) (2018), pg 89.

[4] Saul Rose, Socialism in Southern Asia (1959), pg 144.

[5] Jeanne S. Mintz, Mohammed, Marx, and Marhaen; the roots of Indonesian socialism (1965), pg 7.

[6] De Preanger-bode, January 1, 1911; De Sumatera Post, January 6, 1911.

[7] de Tollenaere. The Politics of Divine Wisdom (1996), pg 240.

[8] “Awas! Kaoem Joernalist!”, August 14, 1918 di Sinar Hindia. See in Journalist Marco (2017), pg 116-125.

[9] Hendrik M.J. Maier, “Phew! Europeesche beschaving! Marco Kartodikromo's Student Hidjo”, in Southeast Asian Studies, Vol.34, No.1, June 1996, pg 184-210.

[10] Boekoe Sebaran Jang Pertama (1916), brochure by Mas Marco Kartodikromo, pg 9.

[11] de Tollenaere. The Politics of Divine Wisdom (1996), pg 298-299.

[12] H.O.S. Tjokroaminoto: Hidup dan Perdjuangannya (1952), Vol 2.

[13] Ibid. Pg 44.

[14] H.O.S. Tjokroaminoto: Hidup dan Perdjuangannya (1952), vol 1. Pg 36.

[15] Leclerc, Mencari Kiri: Kaum Revolusioner Indonesia dan Revolusi Mereka (2011), pg 14.

[16] Lambert Giebels. Soekarno onderdaan: Een biografie 1901-1950 (1999), pg 79-81.

[17] “Anarchisme” in Fikiran Ra’jat, No.2, July 8, 1932; juga Fikiran Ra’jat , No.21, November 18, 1932.

[18] Harry A. Poeze. Tan Malaka : Strijder voor Indonesië's Vrijheid : Levensloop van 1897 tot 1945 (1976), pg 267.

[19] Soe Hok Gie, Di Bawah Lentera Merah (2016), pg 40.

[20] Alimin. Riwajat Hidupku (1954), pg 27.

[21] Lembaga Sedjarah PKI. 1961. Pemberontakan Nasional Pertama di Indonesia (1926). Pg 110-111.

[22] Alimin Prawirodirdjo, Analysis (2015), pg 39 and 31.

[23] “Dunia jeung Jaman Anyar” [Dunia dan Zaman Baru], in Sora Merdika, No. 20, August 17 1920.

[24] McVey. 1he Rise of Indonesian Communism (2006), pg 426.

[25] Tjokroaminoto, Islam & Sosialisme (V print, no year), pg 6.

[26] Kahin, “In Memoriam: Mohammad Hatta, (1902-1980)” in Indonesia, No.30 (Oktober 1980), pg 118.

[27] Musso, Jalan Baru untuk Republiek Indonesia (2017), pg 52.

[28] Jafar Suryomenggolo, Organising under the Revolution: Unions and the State in Java, 1945‒48 (2013), pg 63.

[29] Leclerc, Mencari Kiri: Kaum Revolusioner Indonesia dan Revolusi Mereka (2011), pg 14.

[30] Dingley, The Peasants' Movement in Indonesia (1927), pg 57.

[31] Soe Hok Gie, Di Bawah Lentera Merah (2016), pg 40.

[32] “Russische Nihilisten” in Sinar Djawa, March 28, 1918; April 2, 1918.

[33] “Merebahkan Pemerintah” in Sinar Hindia, March 27, 1919. See Soe Hok Gie, Di Bawah Lentera Merah (2016), pg 97.

[34] “Dunia jeung Jaman Anyar” [Dunia dan Zaman Baru], in Sora Merdika, No 20, August 17, 1920.

[35] Soe Hok Gie, Di Bawah Lentera Merah (2016), pg 40.

[36] “Soesah sekali?” in Soeara Ra’jat, No.3-4, 16 & 28 February 1921.

[37] “Akratie” in Soeara Ra’jat, No.6, March 21, 1921.

[38] “Pembicaraan Buku De Groote denkers der eeuwen”, Sinar Djawa, December 22, 1917. See Soe Hok Gie, Di Bawah Lentera Merah (2016), pg 97.

[39] Soe Hok Gie, Di Bawah Lentera Merah (2016), pg 40.

[40] Soe Hok Gie, Di Bawah Lentera Merah (2016), pg 40.

[41] Larson, Masa Menjelang Revolusi: Keraton dan Kehidupan Politik di Surakarta, 1912-1942 (1990), pg 196-198.

[42] Larson, ibid, pg 369.

[43] Takashi Shiraishi, An Age of Motion (1990), pg 277-278.

[44] McVey. 1he Rise of Indonesian Communism (2006), pg 71.

[45] Leclerc, Mencari Kiri: Kaum Revolusioner Indonesia dan Revolusi Mereka (2011), pg 13-14.

[46] McVey. 1he Rise of Indonesian Communism (2006), pg 478.

[47] VSTP Meeting Minutes. 25/26 December 1925, Hotel Pasar-Pon, Surakarta (untitled manuscript, in Indonesian) pg. 6-7. International Institute of Social History archive. Quoted from McVey. 1he Rise of Indonesian Communism (2006), pg 471.

[48] McVey. 1he Rise of Indonesian Communism (2006), pg 478.

[49] Tan Malaka, Aksi Massa (2013), pg 92 & 99.

[50] Hatta, Kumpulan Karangan (1976), pg 393.

[51] Aidit, Pilihan Tulisan Djilid 1 (1959), pg 20.

[52] Lembaga Sedjarah PKI. 1961. Pemberontakan Nasional Pertama di Indonesia (1926). Pg 8.

[53] McVey. 1he Rise of Indonesian Communism (2006), pg xiii.

[54] Klaas Stutje. “‘Volk van Java, de Russische Revolutie houdt ook lessen in voor U’: Indonesisch socialisme, bolsjewisme, en het spook van het anarchisme” in Tijdschrift Voor Geschiedenis (2017), pg 440.

[55] Harry J. Benda, “The Rise of Indonesian Communism” in The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol.26, No.2, Februari 1967, pg 343.

[56] Arif Dirlik. “Anarchism and The Question of Place: Thoughts From The Chinese Experience”, in Anarchism and Syndicalism in the Colonial and Postcolonial World, 1870–1940 (2010), pg 134.

[57] Saul Rose, Socialism in Southern Asia (1959), pg 144.

[58] Takashi Shiraishi, An Age of Motion (1990), pg 341.