Bima Satria Putra

From River to the Sea

Jewish Anarchist Perspectives on the Palestinian Conflict

בַּיָּמִ֣ים הָהֵ֔ם אֵ֥ין מֶ֖לֶךְ בְּיִשְׂרָאֵ֑ל אִ֛ישׁ הַיָּשָׁ֥ר בְּעֵינָ֖יו יַעֲשֶֽׂה

“In those days there was no king among the people of Israel; each person does what is right in his own eyes.” – Judges 21:25

The only issue in the 21st century that can divide the human population across the world into two camps is the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. When this essay was written, the number of Palestinian deaths due to Israeli bombing and invasion in 2023 passed 11 thousand people (and continues to grow). Millions of people around the world poured into the streets to show solidarity with Palestine while condemning Zionism. Among the ranks, which were still considered strange, were eccentric demonstrators from a group of orthodox Jews whose hats, beards and braided hair were distinctive. They refuse to equate Zionism with Judaism. For them, criticizing Israel does not mean they are anti-Semitic.

Islamic fundamentalism groups in Indonesia have politicized the Palestinian conflict, and this makes the presence of Jews in Palestinian solidarity actions must be suspected. Oversimplified as a war between religions, Jews seem to be made the eternal and main enemy of Muslims. On the opposite side, another strange phenomenon emerged that was no less reactionary, which Noam Chomsky pejoratively called Christian-Zionism. Those Christians who may not claim to be so, but with closed eyes have supported and justified Israeli militarism based on a Biblical interpretation of the “promised land” claim. For these two fanatical camps, Jews opposing the state of Israel and defending Palestinians could be a sign that the end is near. In fact, one segment of Jewish politics that opposes the project of establishing a modern Israeli nation-state is anarchists.

These two subjects (“Jews” and “anarchists”) are most often misunderstood. The first was seen as a barbaric and cursed religion, the second was misinterpreted as political chaos and violence. The combination of the two, anarchist-Jewish, suggests the worst kind, or an adjective with a negative connotation that cannot be found in any dictionary. In this essay I will explain that this kind of revolutionary possibility really does occur.

Biblical Interpretation

Anarchists have traditionally been skeptical of or strongly opposed to organized religion. Even so, some anarchists have provided religious interpretations and approaches to anarchism. Postdoctoral fellow at Bar Ilan University in Israel, Hayyim Rothman, in his book No Master But God (2021) has summarized eight rabbis and Jewish thinkers who explicitly refer to anarchist ideas in articulating the meaning of the Torah, traditional practices, Jewish life, and modern Jewish missions. Using material from both Hebrew and Yiddish, Rothman's work is one of the rare, most comprehensive references to Anarcho-Judaism available in English.

According to Rothman's explanation, Anarcho-Judaism emerged as a historical trend that began during the last two decades of the nineteenth century, in response to the oppression of Russian Jews, and lasted during the period of the Jewish Enlightenment called haskalah (הַשְׂכָּלָה), which transformed modernization into a project of Jewish liberation. As a religious variant of anarchism, Anarcho-Judaism opposes all forms of centralized institutions of power, viewing them as problematic and advocating non-state Jewish institutions for self-management based on political and economic egalitarianism. This trend can even be traced back to ancient times in the Tanakh.

Professor Amnon Shapira of Ariel University in Israel, has compiled primary material on Anarcho-Judaism in Anarkhizm Yehudi Dati [יתד ידוהי "םזיכרנא"] published in Hebrew in 2015. In it, he states that the Book of Exodus (שמות) depicts an Israeli society without centralized government mechanisms, governed by the “anarchistic” legal code of ancient society, and operated based on mental and voluntary obedience to Torah law. This system lasted until they occupied the promised land, when they lived surrounded by state societies (such as the Philistines, Midianites, Moabites, and Canaanites) as told in the Book of Judges (ספר שופטים).

Egyptologist and maximalist biblical scholar Kenneth Kitchen in On the Reliability of the Old Testament (2003) explains that in times of crisis, the people of Israel will be led by ad hoc tribal leaders, called judges (shoftim). In the biblical narrative, the judge is described as a leader whose position is not inherited, coming from different tribes of Israel, chosen by God who is angry because his people worship the gods of other nations. One of them is the judge Gideon, who rejected the request of the Israelites for the establishment of Gideon's rule: "I will not rule over you, nor will my son rule over you, but LORD will rule over you" (Judges 8:23).

The Israelites again made the same request in the time of the Prophet Samuel: "Give us a king to rule over us, like other nations." This request made Samuel upset, because the Israelites wanted to imitate the formation of a kingdom like the nations around them who did not know God. The Lord said with reluctance and jealousy to Samuel: "Listen to the words of the people in everything they say to you, because it is not you they reject, but I am the one they reject, so that I do not become king over them." God asked Samuel to remind them of the consequences of the establishment of the state: taxes, conscription, slavery and authoritarianism.

Natan Hofshi commented on the establishment of human kingdoms in Samuel's time as a denial of divine sovereignty: “There is not a single king, good or bad, even the best of them, who conforms to God's wishes - they displease Him.” The biblical narrative tells that the Kingdom of Israel was divided with the founding of the kingdom of Judah, and these two tiny kingdoms were destroyed. Although there is much debate about the historical validity of the kingdom, the book of the twelve prophets (שנים עשר) which makes up the end of the Old Testament is completely anti-authoritarian in tone and condemns the arbitrariness of Israel's rulers.

For Jewish anarchists, the declaration of independence is different from the declaration of state formation. There will be no such thing as freedom within the state, because the state involves coercive mechanisms and instruments of violence. Rabbi Shmuel Alexandrov explained that Israel “had no static [statehood] goals in its [shofar] statement.” Quoting Zechariah 4:6, Rabbi Alexandrov stated that freedom can only be achieved, “not by [military] might or [physical] power, but by My spirit,” namely the word of the Lord of the universe.

In this way, Jewish anarchists understand the “Kingdom of God” (מַלְכוּת שָׁמַיִם) literally. In the view of Rabbi Avraham Yehudah Heyn, “‘Make Him [God] king in heaven and on earth and in the four corners’—this is not just a metaphysical idea.” The existence of kings and human governments belies God's authority, so recognizing God as the only king means the absence of human government. The book of Isaiah (יְשַׁעְיָהוּ) 33:22 confirms this: “For the Lord is our Judge, the Lord is the one who gives us the law; God is our King.” When there is a “king” in heaven, there will no longer be a need for a king consisting of flesh and blood.

The Birth of Zionism

With the destruction of the Israel-Judah kingdom, Israel's national identity became extinct. But Jews survived and passed on a collective cultural memory that became the foundation for the birth of new Abrahamic religions: Christianity and Islam. For most of AD history, most Jews lived in diaspora outside the Land of Israel. Diasporas occur due to various historical conflicts and gradual processes that occurred over centuries, starting with the destruction of Israel by the Assyrians, the destruction of Judah by the Babylonians, the destruction of Judea by the Romans, and the subsequent rule by Christians and Muslims. A series of Jewish depopulations and exoduses occurred.

Under Eastern Roman (Byzantine) rule, the entire region of Philistia, Judea and Samaria was reorganized into Palaestina Prima. The term Palestine then continued to be used, including by Jews (and the initiators of Zionism) as a geographical unit of their land of origin, until that use stopped with the founding of the state of Israel in 1948. Bibles published until the beginning of the 20th century also featured a map of the "Holy Land of Palestine ” as their appendix, before a recent Bible map corrected it as Israel.

The Jewish diaspora organizes the Jewish composition into several types: Ashkenazi (regions of the Roman Empire, especially Russia and Eastern Europe); Sephardi (Iberian Peninsula, i.e. Spain and Portugal); and the Mizrahi who remained in Palestine, who were divided between the Mashriqi, Asiatic Jews who settled in the Middle East and the Maghrebi in North Africa. These groups have parallel histories sharing many cultural similarities as well as a series of massacres, persecution and expulsions, such as the expulsion from England in 1290 and from Spain in 1492. Occasionally, a small portion of Jewish migration returned to Palestine, long before the first Zionist aliyah (עֲלִיָּה ) in 1885. However, they constituted a minority group and were not interested in taking power, or establishing a Jewish government of any kind. While outside Palestine, Jews became subjects of many nations, and were essentially stateless. It would chronicle a rich and highly diverse, but essentially anarchistic, Jewish history.

As a result of increasing antisemitism in Europe, such as the Dreyfus case in France and the Ashkenazi anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire, the Zionist movement was born. The original originator was Theodor Herzl, an Austro-Hungarian Jew, who did not believe in Jewish liberation. According to him, anti-semitism cannot be fought, but can only be avoided by the Jews leaving Europe. Herzl spoke no Hebrew or Yiddish, had no Jewish education, and was even accused of being an atheist.

Herzl’s proposal for an ethno-nationalist state in Palestine in his essay Der Judenstaat (1895) stated the limitation of power and the neglect of priests. “We will keep our priests in their temples in the same way as we will keep our professional soldiers in their barracks,” and “they must not interfere in the administration of the state that grants them privileges.” According to him, the involvement of priests “will cause difficulties outside and within them.” It is natural that the rabbis, who were accused of being reluctant to lose their privileges, were the first group to most vehemently oppose his ideas.

In 1897, German rabbis attempted to stop the Zionist Congress. They argue that the intention to establish a Jewish state goes against “the messianic promises of Judaism.” Jewish anarchists usually interpreted the coming of the Messiah as an implementation of religious anarchism, although the German rabbis of the time were the ones who thought it would take the form of a state. Therefore, they view the Zionists as wanting to realize the Messiantic ideal without a Messiah. No less important, the rabbis are concerned that the movement is actually fueling further anti-Semitism. Because Herzl's book was published in a language that non-Jews could understand, the rabbis feared that anti-semitism would take the form of supporting the Zionist agenda, namely justifying that Jews should be expelled from Europe (a motive that was indeed realized). Due to opposition from the rabbis, Herzl decided to change the location of the First Zionist Congress to Basel, Switzerland.

Zionism was the same seed as the emergence of nationalism among European nations in the mid-19th century. At that time, European Christians began to identify themselves with nationalities that they felt compatible with, celebrating their history, distinctive language and traditions, and self-determination. In such a situation, Jews fell into an existential crisis where they began to become strangers in the land they had inhabited for a long time. Some Jewish figures support assimilation where they live. Jews in Constantinople, for example, would consider themselves Turks of the Jewish faith, in Tbilisi as Georgians, and in Madrid as Spaniards. Instead, Herzl proposed Jewish nationalism, a nation separate from Europe, as a solution to anti-semitism.

Because they became a separate nation, the Jews needed land and territory. Herzl's proposal: Argentina or Palestine. At the 1897 Zionist congress, it was determined that the "national home" of the Jewish people that would be created would be Palestine. Even so, “national home” is an ambiguous term that can refer to a state or a ‘spiritual center’. This is where Zionism's division lies. Although Zionism in today's popular discourse refers to the creation of a Jewish state, not all camps in the history of the Zionist political movement supported an ethno-nationalist state.

In the early 20th century, Zionists split into Political Zionists supporting the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine, Cultural Zionists who pushed for a cultural revival in Palestine regardless of diplomatic circumstances, and Territorialist Zionists for autonomous self-governing communities wherever Jews existed. Rejection of state formation is part of Zionist aspirations. Even though they were small, they became a legitimate part of the Zionist movement, until finally Zionism was taken over by bourgeois nationalists. The World Zionist Organization (WZO) itself did not explicitly call for the creation of a Jewish state until 1942.

Jewish Anarchist Criticism

Jews were perhaps one of the most violent and active groups in the long history of anarchism. Several leaders of anarchism, such as Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Murray Bookchin, David Graeber, and Noam Chomsky, are all Jews. Since the beginning of the emergence of Zionism, Jewish anarchists have persistently positioned themselves as opponents of the first faction of the Zionist project. Some left-wing Zionists such as Yitzhak Tabenkin, Berl Katznelson and Mark Yarblum were largely influenced by libertarian socialists such as Peter Kropotkin and Leo Tolstoy. Joseph Trumbledor, who became a hero of Israel's right wing, openly declared himself an anarcho-communist. The kibbutz agricultural commune movement initially brought anarchist ideology to the Middle East in the early 20th century, carried out by large waves of Jewish emigrants from Eastern Europe arriving in Palestine.

Anarchists have various alternative visions of Palestine, ways to realize it without violence, to reconciliation for the possibility of coexistence. For example, R. Yaakov-Meir Zalkind, who belongs to the Cultural Zionist faction. Zalkind was a figure in Jewish anarchist circles in London and the editor of Arbeter Fraynd [Friend of Labour], the most important Yiddish-language anarchist journal of its time. The Arbeter Fraynd journal, which he manages, has become an arena for controversial debates about Anarcho-Zionism. One writer who identified himself as a 'Zionist anarchist', for example, stated that Zionism sought to resettle 'homeless Jewish laborers', not to establish a state, and that both movements opposed capitalism while promoting liberation and emphasizing human agency in achieving it.

Zalkind separated himself from the Zionist movement. But he envisaged the establishment of an autonomous, anarcho-communist Jewish community in Palestine, which would be “the cradle of a new society living according to the noblest ideals of Judaism and humanity.” Palestine should become a cultural center for Jews throughout the world, where a handful of diaspora Jews can be welcomed, but not the majority of immigrants. Moreover, Zalkind rejected the transformation of Zionists into a political movement focused on Palestine, because Zionism instead solved the Jewish refugee problem by displacing the local Arab population and in turn turning them into new refugees. If this happens, he wrote, “our first step into the ethical world of colonialism becomes a shameful marker for the Jewish people that can never be erased, this is the blackest blood ever written in the dark history of colonial politics.”

Isaac Nachman Steinberg was a Russian Jewish socialist. Although he did not openly claim to be an anarchist, according to Rothman, his thinking had a libertarian tone. Steinberg emphasizes the diaspora aspect and states that throughout history, Jews have always been “decentralized, voluntary and cooperative.” Echoing Samuel's frustration, Steinberg warned that Jews “not imitate the world around them.” He recommended that Jews adhere to diasporaism which for thousands of years was anti-political, without a state, a seed that developed in a new land. Regarding Palestine itself, Steinberg subordinated it geographically. “Palestine is wherever the Jewish spirit rages,” he said. Moreover, this diaspora experience has lessons to be learned:

“In their wanderings around the world, the Jewish people saw again and again how states and static civilizations [states] emerged, grew, reached the pinnacle of power and glory, and then collapsed due to 'sin' and evil… [and] cruel tyranny. [Jews] who have seen what non-Jews are doing to their state, should not be easily provoked into similar actions.”

Rabbi Shmuel Alexandrov, a Jewish libertarian and pacifist from Belarus, dragged the diaspora further to erase state borders and advocate cosmopolitanism. He made the story of when God destroyed the inhabitants of the Tower of Babel with a concentrated population, a single language, and filled with civilizational ambitions in the Book of Genesis (בְּרֵאשִׁית). When they are made to scattered them across the earth, Rabbi Alexandrov elaborating this story as the dissolution of national identity. He declared that “the new Zionists only want to establish a Jewish state,” as “the furthest thing from our religion.” Rabbi Alexandrov used the Book of Isaiah (יְשַׁעְיָהוּ) 2:3 to make Palestine simply the “capital” of the Jewish cultural and religious renaissance, filled with a cultural elite. But he denied that the center served as a prelude to a general gathering of Jewish immigrants.

The Book of Isaiah (יְשַׁעְיָהוּ) chapter 2 is also considered important in the vision of Jewish Rabbi Aaron Shmuel Tamaret who was born in Belarus. Israel's transformation into a state, with its nationalism and militarism, actually contradicts the Prophet Isaiah's vision of Zion: "nation will no longer lift sword against nation, and they will no longer learn war." Rabbi Tamaret denounced the Zionist attitude of nationalism, patriotism, statism, and militarism as “a monkey-like imitation of Western customs.” Israel, he stressed, must be steadfast in its commitment to Abraham's mission. He must resist the temptation of foreign gods and destroy the idols called nation, land and state.

Another figure we need to highlight is the Jewish anti-militarist Natan Hofshi. Even though he was neither a scholar nor a rabbi, as someone who lived in Palestine since 1909 and witnessed the founding of the state of Israel until his death in 1980, his point of view is clearly interesting and clearer. A Zionist who later embraced anarchism, Hofshi was the first to be imprisoned by the Israeli government for refusing conscription, proposing that Jewish migration to Palestine be postponed and even developing intimate sympathetic relations with Palestinian Arabs.

In the 1920s, amid escalating Jewish conflict with Arabs, Hofshi saw the growth of Zionism's militancy as a setback because it "tried to instill in us the belief that we would achieve our national goals with blood and weapons, with murder and destruction." He sees Zionist militarism as an attempt to “build up the land of Israel and even make a deal with the devil if necessary.” Hofshi does not deny that Judaism emerged from a biblical warrior culture, but he maintains that Jeremiah and the other prophets completely overturned the way of Esau's sword. The Zionist leadership thus he argued had put the Jewish tradition of non-violence in the trash when they decided to establish a sovereign Jewish State despite Arab protests and the resulting threat of war.

Anarcho-Judaism relies on its arguments for a religious anarchism that today seems revolutionary because it opposes the Israeli government. But a hundred years ago, this kind of tendency was considered conservative and old-fashioned by “reformist” Jewish nationalists, because they tried to stick to the Torah. Proponents of Zionism had difficulty deriving justification from Judaism, and were basically aware of it. Therefore, they completely base the legitimacy of the formation of the state of Israel on international support and recognition alone.

Other prominent Jewish anarchists, both atheists and secularists, stood on the same side as their more religious anarchist brethren to criticize Zionism without using the scriptures. Emma Goldman, in her 1938 essay supported the right of Jews settled in Palestine to work and develop as a people. Even so, she claims to have long "opposed Zionism as the dream of capitalist Jews throughout the world to establish a Jewish State with all the facilities, such as government, law, police, militarism, etc." Goldman accused the “Jewish State machine” is only “protecting the privileges of the few over the many.”

Meanwhile, for an intellectual giant like Noam Chomsky, his commitment cannot be doubted. Chomsky himself grew up in a family that supported labor Zionism, decided to become an anarchist as a child and even lived in a collective agricultural commune in Mandatory Palestine before the declaration of Israel in 1948. Even so, he has become one of the most influential commentators today on Israel and Palestine. Chomsky analogized the treatment of Gaza as worse than apartheid in South Africa, and supported the boycott, divestment and sanctions movement against Israel. The Zionist state seemed to him the absolute embodiment of colonialism:

“...the story of Palestine from its beginnings to the present is a simple story of colonialism and dispossession, but the world treats it as if it is a multifaceted and complex story—hard to understand and even harder to solve. It's true, the story of Palestine has been told before: European settlers came to a strange land, settled there, and committed genocide or expelled the native population. The Zionists in this case are not doing anything new.”

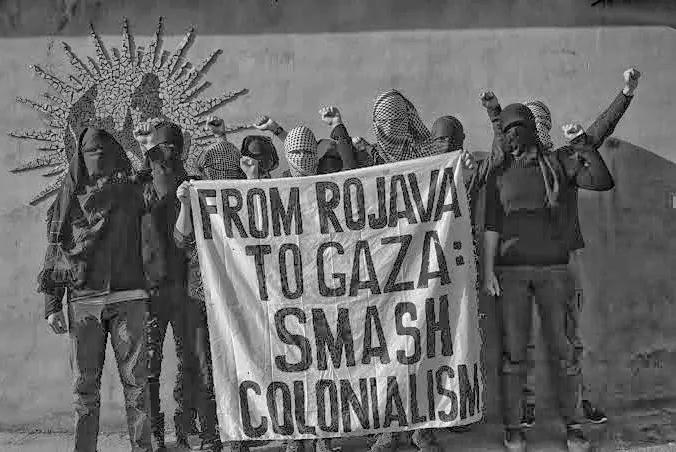

Anarchists in Israel today are involved in demonstrations, destroying fences and border walls, distributing aid to Palestinians, and campaigning against conscription. Even though their power is small and insignificant, their aspirations and activities are quite disturbing and leave an impression, to the point that Netanyahu often labels many of his political opposition "traitors", "leftists" and "anarchists", even though those he appoints are not anarchists at all. Israeli anarchists are the paveers of Jewish revolutionary politics, Israel's enemies from within, strategic allies (in both theory and practice) in genuine Palestinian liberation. As both Jewish and Arab anarchists have fought for on both sides of the border wall, solidarity unites the two.

Overall, Anarcho-Judaism has provided a radical alternative that challenges fundamentalist religious discourse as well as a solution to resolve long-standing conflicts that continue to claim victims.

No State Solution

The Jewish anarchist position transcended the political and cultural boundaries of the conflict in Palestine. Ambivalence may arise from playing on both feet. But let's try to consider their opinions seriously. Jewish anarchists have never denied the right to reside in or visit Palestine as the Jewish “homeland” or holy land. They agree with the existence of cultural centers and agricultural communes, but deny that this should be realized through concentrated mass-scale migration, let alone the establishment of states, through expulsion, violence and land confiscation, which for them is contrary to the teachings of Judaism. In short, it is not impossible for Jews to be anti-Zionists, supporters of Palestinian national liberation, reconciliation of Jews with Arabs, while supporting the dissolution of the state of Israel.

Murray Bookchin, perhaps the least “problematic” of all the Jewish anarchists discussed here. Bookchin abandoned Marxism for anarchism, then abandoned anarchism again because he apparently couldn't stand criticism. Bookchin then formulated his own libertarian socialist alternative through a project of communalism that he called libertarian municipalism. In short, he proposed an alternative non-state institution, with direct democracy from the bottom up through autonomous communes and connected through confederations.

Bookchin's 1986 essay has been accused of being an excuse for Zionists. By exerting his energy and concentration criticizing the authoritarianism of the leaders of Arab countries, especially with a few historical errors in his essay, he actually gave the impression of defending [state] Zionism. Yet he also stated that “there is much to criticize about Israeli policy, especially under the Likud government that orchestrated the invasion of Lebanon.” As a Jew, it seems that Bookchin wants to emphasize his position as a balance in the middle, by exposing a historical reality that cannot be ignored: the expulsion of Jews from Arab countries since the 1920s.

The above should not stop us from highlighting his consistent vision of democratic confederalism: “For many years I have hoped that Israel or Palestine could develop into a Jewish and Arab confederation like Switzerland, a confederation in which both peoples could live in peace with each other and develop their culture creatively and harmoniously.”

Is such a non-state solution possible in Palestine? Currently, that possibility seems to have been answered in the ethnic Kurdish region of Syria. The Kurdish and Palestinian struggles have a long history. Rojava militants, including Abdullah Öcalan, the Kurdish national liberation leader, trained in camps in the Bekaa valley in eastern Lebanon during the 1980s and maintained ties with Fattah and a number of other Palestinian parties and militias. Bookchin became highly influential among Kurds after Öcalan adopted his ideas for advancing a vision of “democratic confederalism,” which the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) tried to implement in northeastern Syria.

In 2013, a social revolution was realized when the Syrian civil war broke out. Bookchin's proposal applies to Rojava, home to sizable ethnic Kurdish, Arab and Assyrian populations, with smaller ethnic Turkmen, Armenian, Circassian and Yazidi communities. The institution of the confederation has been appreciated for providing much greater autonomy for each ethnic community to govern itself at the commune level. This is something that is difficult to realize in state structures which usually become a vehicle for the struggle for a centralized monopoly of power by certain ethnic groups. Moreover, this is openly manifested in the state of Israel, which is fully intended as an ethno-nationalist state.

What is the lesson from all this? I think the Jewish experience with Zionism was, ironically, similar to Nazi Germany's fascism: the doom of the ambition to create an ethnically exclusive nation-state. Jewish anarchists have warned against this. We must listen to their advice. Fortunately, national liberation efforts in recent decades have been reconsidered by the Maya people of Chiapas, Mexico and the Kurds of Rojava, Syria. National liberation does not always have to take the form of a state.

Bookchin's confederalism, which Öcalan uses, is a completely non-state institution, which might be able to fill the gap in the non-state solution platform that has been proposed by anarchists, both Jews and Palestinian Arabs. The most recent articulation is currently contained in The No-State Solution: A Jewish Manifesto (2023) by Daniel Boyarin. His ideas almost represent a timeline of the history of Anarcho-Judaism thought that has emerged, such as the spirit of preserving the diaspora, which is displayed large on the opening page: "Wherever we live, there is our homeland."

Examining most of the early Zionist thinkers, including their bold interpretations of Herzl, Boyarin concludes that they “explicitly envisioned an autonomous Jewish national territory within a state composed of other peoples as well.” His proposal is somewhat contradictory to the title of the book. But the idea can be easily refined if we combine Boyarin with Bookchin, namely a confederation (not a state!) of Jews and Arabs, and all people from different backgrounds, as in Rojava. If this sounds unrealistic, I quote Boyarin, who at the end of his book:

“If we want the Jewish people to continue to be a meaningful entity, a diasporic people with the culture and ability to deeply care and fight for other oppressed peoples (especially for the people we have oppressed, Palestine), we must make it happen: הדגא וז ןיא וצרת םא! [If you want, it's not a dream!]”

Bima is an Independent researcher, author of Dayak Mardaheka: History of a Stateless Society in the Interior of Kalimantan (2021). Still committed to writing even though he is serving a 15 year prison sentence. Take the time to read Bima’s proposal on Firefund.

Recommended Reading

-

There are no references to Jewish anarchism in Indonesian. But primary sources for the ideas of Anarcho-Judaism can be read through:

-

Hayyim Rothman. 2021. No masters but God: Portraits of anarcho-Judaism. Manchester University Press.

-

Amnon Shapira. 2015. Anarkhizm Yehudi Dati: Iyyun Panorami ba-Gilgulo shel Rayon mi-Yemey ha-Mikra we-Hazal, Derekh Abarbanel, we-ad ha-Et ha-Hadash [Jewish Religious Anarchism: Chapters in The History of An Idea, From Biblical and Rabbinic Times, Through Abravanel, Through The Modern Era]. Ariel: Hotseyt Ariel University.

-

For a history of Jewish anarchist thought and movements:

-

Anna Elena Torres and Kenyon Zimmer (eds). 2023. With Freedom in Our Ears: Histories of Jewish Anarchism. University of Illinois Press.

-

Mina Grauer. "Anarcho-Nationalism: Anarchist Attitudes towards Jewish Nationalism and Zionism", in Modern Judaism, Vol.14, No.1 (Feb., 1994), p. 1-19 (19 pg.). Published by: Oxford University Press.

-

Ridhiman Balaji. 2021. “A Zionism opposed to a Jewish state,” in: Anarcho-Syndicalist Review #83, Summer, 2021.