Mèo Mun

Queerphobia in Vietnam

Is queerphobia in Vietnam a mere product of colonialism, and does it matter?

There is a tendency in some post-colonial societies to blame all social ailments, such as queerphobia, sexism, and misogyny, on colonialism and Western imperialism. Whilst the evils and destructiveness of colonialism are indubitably pervasive, such reductive thinking is overly simplistic, and can be detrimental to marginalised groups in post-colonial societies.

Let’s explore this in the context of gender and sexuality liberation in modern Vietnam. Some Vietnamese claim that homophobia is solely a product of French colonialism, often citing the fact that the Vietnamese equivalence of the f-word — “pêđê” — originated from the French “pédéraste.” But is it truly the case that Vietnamese society was free of queerphobia before French colonisation? And for those fighting for liberation today, does it matter?

Pre-French colonisation, Vietnam was under the influence of Confucianism, which became the prominent ideology during the Lê Dynasty (15–18th century). An ideology that upholds patriarchy and places the burden of preserving the bloodline on men will necessarily come with a certain degree of homophobia. Historical records speak of prince Lê Tuân (1482–1512), whose preference to dress in women’s clothing cost them the favor of king Lê Hiến Tông (1461–1504), and subsequently the throne. To this day, many still attack queer people using Confucian teachings. This is, of course, a logical fallacy appealing to tradition; it should be rejected wholeheartedly. In the olden days, Confucianism was used to justify the divine right of kings; today, we cannot let violence against marginalised groups be justified in the name of culture, religion, and tradition. In modern parlance, bigots often combine this with an appeal to nature, where they cherry-pick a slice of life from the animal kingdom and apply it to humans, ignoring the fact that homosexual behaviour, not necessarily sex, has been documented in hundreds of species.

Nowadays, some groups amongst the Vietnamese LGBTQIA+ community are beginning to expropriate queerphobic slurs for use in safe spaces: “Rất đỗi bê đê”, “Ê Bê Đê cho ly cà phê”, “The Pónk Fellow” are a few prominent examples. However, the process of reclaiming slurs is complex and emotional for the targeted groups, and queer people’s expropriating certain slurs is not a green light for non-queer people to use those slurs at will.

As progress for LGBTQIA+ rights improves in Vietnam, so does the reactionary backlash against it. Queerphobes, such as those amongst nationalist and red-pill groups, are also evolving their vocabulary. Let’s have a quick Vietnamese lesson on a few common slurs thrown around by young Vietnamese:

-

“Làng Gốm Bát Tràng”, or it short form “Làng Gốm”:

“Làng Gốm Bát Tràng” is a town of pottery makers in the outskirts of Hanoi, which has the misfortune of sharing the same initial with the term LGBT. In the beginning, it was used as a way to avoid automatic content filtering, but has since become a full-fledged slur. -

“LGTV”:

The Vietnamese language is pretty malleable, and the initials for the name of a TV brand are close enough to “Làng Gốm”. People would come to queer spaces and post this intentional misspelling of LGBT as thinly veiled aggression. -

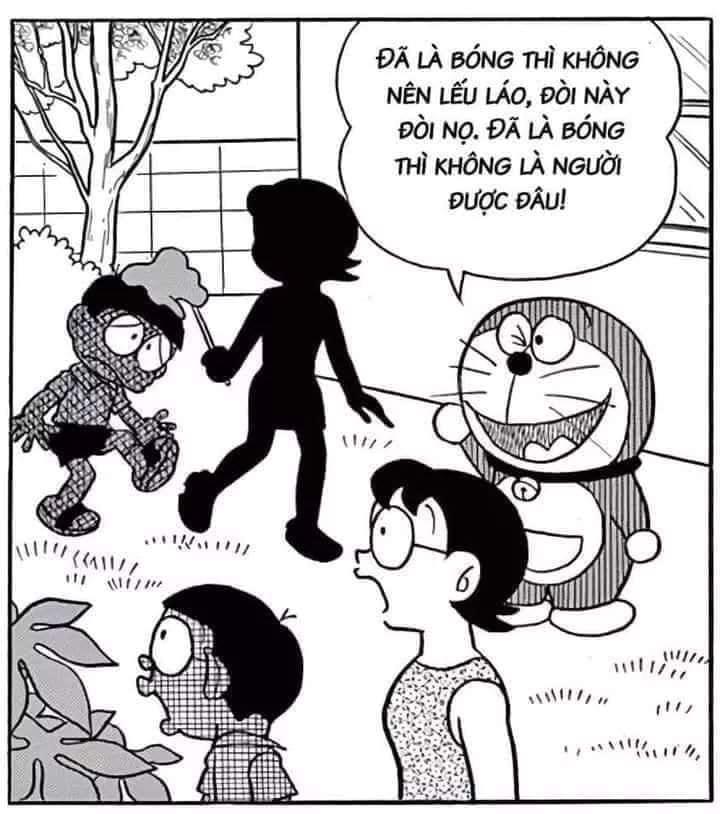

“Bóng”:

Yes, another slur. Here’s a popular remixed Doraemon panel where it’s implied that queer folks (“bóng”) are somehow inferior sub-humans.

The view is that queer people should be content with the status quo, and should not be so arrogant when demanding their rights. To these reactionaries, the mere acknowledgment of queer existence is unfathomable, and any further attempt at liberation is perceived as “supremacy” to be resisted at all cost.

-

“Thổ tả”:

The Vietnamese phrase for “cholera” sounds almost similar to “cánh tả” — leftists, and hence also used as a slur. Gender and sexuality equality initiative often comes from liberal, pro-democracy NGOs, and is looked upon with suspicion by Vietnamese nationalists. -

“Nước Nga là thành trì cuối cùng”

Why do some Vietnamese often drop this seemingly random statement “nước Nga là thành trì cuối cùng” (“Russia is the last bastion”) when discussing same-sex marriage? It is a dog whistle, referring to Russia’s restrictive policies toward queer people, and they don’t mean it as a bastion against the Nazi, but queer people.

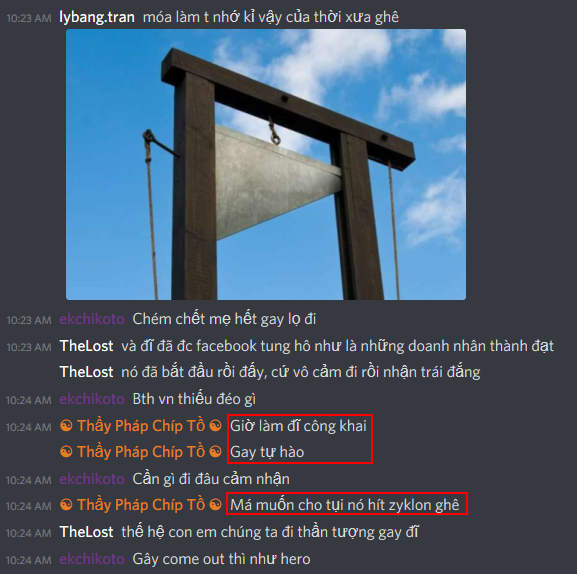

More often than not, this rhetoric leads people down the vile path to fascism. Nowhere is this clearer than in Vietnam’s small but rapidly expanding red-pill movement. In a private red-pill Discord server, the members nonchalantly discuss gassing the gays with Zyklon:

That’s horrifying, yet not surprising of red-pillers. Alarmingly, many Gen-Zs in Vietnam today would tell you that they know at least one friend or family member who is familiar or interested in red-pill ideas.

Another reactionary force is the nationalists, who are much more diverse and numerous, with similar attitude toward queer people. Recently, a 9th-grade high school student rightfully pointed out, in a Tiktok video, that Vienam’s Giáo Dục Công Dân (Citizen Education) textbook is homophobic, because it says: “The state does not recognise marriages between persons of the same sex.”

For this simple observation, she immediately got dog-piled. One of the reasons Vietnamese nationalists are against same-sex marriage is that they view young people as the engine of economic growth, and thus are horrified of losing that population makeup due to queer people’s not making babies. Nationalists would prefer to keep same-sex marriage in the limbo between not being criminalised but still unrecognised, for the sake of the economy. There are two logical fallacies in their argument: appeal to law and appeal to nature. Economic development should not depend on the exploitation of young people. As anarchists, we recognise that the institution of marriage is deeply rooted in the exploitation and economic oppression of women, but at the moment, the legalisation of same-sex marriage is vital, for it will afford queer people life-altering rights related to insurance benefits, inheritance, and medical emergency.

In another recent incident, a group of high school students performed a dance on the 90th birth date of the Hồ Chí Minh Communist Youth Union. They faced so much vitriol from Vietnamese nationalists that they had to take the video down. Their sin: waving and saluting to the rainbow flag on stage. Nationalists claimed that these students had violated the solemnity of the occasion, that flying the rainbow flag next to the national flag, next to Hồ Chí Minh himself, was a blasphemy worthy of harassing minors.

In both instances, the dog-piling was initiated or amplified by nationalist groups with hundreds of thousands of followers. Of all the affiliated organisations in Vietnam, the Hồ Chí Minh Communist Youth Union should be the one leading the charge in youth liberation as well as gender and sexuality liberation, yet they did not defend these children in any meaningful ways. If you cannot fly a flag that represents your gender, sexuality, and humanity, in a revolution, is that revolution worth fighting for?

To blame all social issues on colonialism and Western imperialism is not at all productive, and helps perpetuate the myth of the noble savage. Queerphobia had existed in Vietnamese society long before French colonisation, and is gravely harming Vietnamese queer people today. It is tempting to rid ourselves of responsibility and blame all problems on our oppressors, but by doing so we will inevitably victimise the most vulnerable, the most marginalised of us. A large part of autonomy is responsibility, and present-day Vietnam needs to account for the many hardships with which its queer people are faced. Any vision of anarchy or a communist society is incomplete without taking into account all oppressed groups.